"Not only my flesh, but my heart also, was involved in the emotion which it stirred."

Queer history has been so thoroughly and systematically not just skipped over in the history books but deleted from the primary sources that you’re lucky if someone, even someone queer, knows about Harvey Milk let alone anything queer that happened pre-Stonewall.

Speaking of Stonewall, Stonewall was an unquestionably important event in our movement for rights and liberation, but it does not, despite its tagline, mark the beginning of the modern queer liberation movement. I would put that marker a hundred years earlier when a handful of poets and scholars and scientists (it was pretty common for someone to be all three back then) in England and Germany and, more tentatively, in the U.S., spurred by their study of ancient Greece and the Italian Renaissance, started to let their feelings of same-sex desire come to the surface and then to find each other and compare notes.

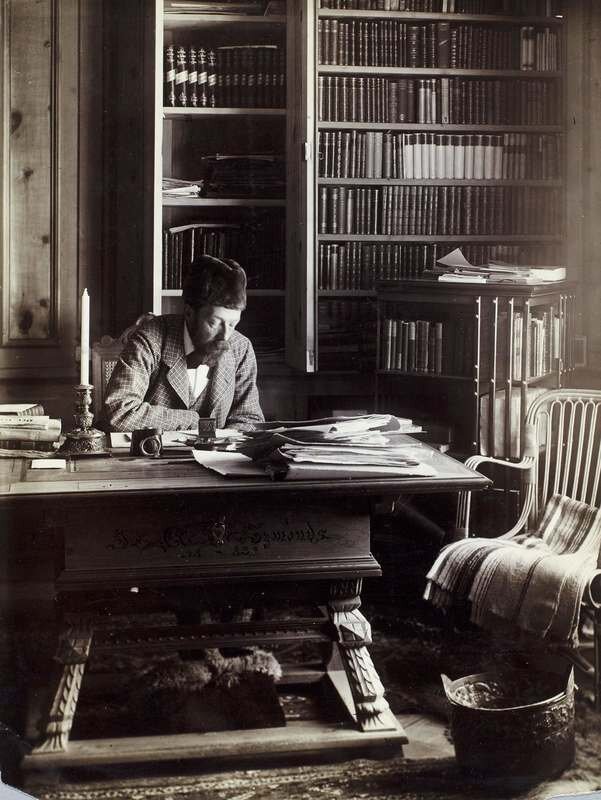

John Addington Symonds, whose birthday is today, wrote his Memoirs around 1890. It’s the first known gay autobiography, and it’s very moving. His account of what we would now call “coming out to myself” is immediately recognizable from over a hundred years’ distance. This stuff should be, is to me, scripture:

“It was my primary object when I began these autobiographical notes to describe as accurately and candidly as I was able a type of character, which I do not at all believe to be exceptional, but which for various intelligible reasons has never yet been properly analyzed. I wanted to supply material for the ethical psychologist and the student of mental pathology, by portraying a man of no mean talents, of no abnormal depravity, whose life has been perplexed from first to last by passion — natural, instinctive, healthy in his own particular case — but morbid and abominable from the point of view of the society in which he lives — persistent passion for the male sex.

“This was my primary object. It seemed to me, being a man of letters, possessing the pen of a ready writer and the practised impartiality of a critic accustomed to weigh evidence, that it was my duty to put on record the facts and phases of this aberrant inclination in myself — so that fellow-sufferers from the like malady, men innocent as I have been, yet haunted as I have been by a sense of guilt and dread of punishment, men injured in their character and health by the debasing influences of a furtive and lawless love, men deprived of the best pleasures which reciprocated passion yields to mortals, men driven in upon ungratified desires and degraded by humiliating outbursts of ungovernable appetite, should feel that they are not alone, and should discover at the same time how a career of some distinction, of considerable energy and perseverance, may be pursued by one who bends and sweats beneath a burden heavy enough to drag him down to pariahdom. Nor this only. I hoped that the unflinching revelation of my moral nature, connected with the history of my intellectual development and the details of my physical disorders, might render the scientific handling of similar cases more enlightened than it is at present, and might arouse some sympathy even in the breast of Themis for not ignoble victims of a natural instinct reputed vicious in the modern age. No one who shall have read these memoirs, and shall possess even a remote conception of my literary labour, will be able to assert that the author was a vulgar and depraved sensualist. He may be revolted; he may turn with loathing from the spectacle. But he must acknowledge that it possesses the dignity of tragic suffering. . . .

“In the spring of 1865 we were living in lodgings in Albion Street, Hyde Park. I had been one evening to the Century Club, which then met near St Martin le Grand in rooms, I think, of the Alpine Club. Walking home before midnight, I took a little passage which led from Trafalgar into Leicester Square, passing some barracks. This passage has since then been suppressed. I was in evening dress. At the entrance of the alley a young grenadier came up and spoke to me. I was too innocent, strange as this may seem, to guess what he meant. But I liked the man's looks, felt drawn toward him, and did not refuse his company. So there I was, the slight nervous man of fashion in my dress clothes, walking side by side with a strapping fellow in scarlet uniform, strongly attracted by his physical magnetism. From a few commonplace remarks he broke abruptly into proposals, mentioned a house we could go to, and made it quite plain for what purpose. I quickened my pace, and hurrying through the passage broke away from him with a passionate mixture of repulsion and fascination.

“What he offered was not what I wanted at the moment, but the thought of it stirred me deeply. The thrill of contact with the man taught me something new about myself. I can well recall the lingering regret, and the quick sense of deliverance from danger, with which I saw him fall back, after following and pleading with me for about a hundred yards. The longing left was partly a fresh seeking after comradeship and partly an animal desire the like of which I had not before experienced. The memory of this incident abode with me, and often rose to haunt my fancy. Yet it did not disturb my tranquillity during the ensuing summer, which we spent at Clifton and Sutton Court. Toward autumn we settled into our London house, 47 Norfolk Square, Hyde Park. Here it happened that a second seemingly fortuitous occurrence intensified the recrudescence of my trouble. I went out for a solitary walk on one of those warm moist unhealthy afternoons when the weather oppresses and yet irritates our nervous sensibilities. Since the date of my marriage I had ceased to be assailed by what I called "the wolf" — that undefined craving coloured with a vague but poignant hankering after males. I lulled myself with the belief that it would not leap on me again to wreck my happiness and disturb my studious habits. However, wandering that day for exercise through the sordid streets between my home and Regent's Park, I felt the burden of a ponderous malaise. To shake it off was impossible. I did not recognise it as a symptom of the moral malady from which I had resolutely striven to free myself. Was I not protected by my troth-pledge to a noble woman, by my recent entrance upon the natural career of married life? While returning from this fateful constitutional, at a certain corner, which I well remember, my eyes were caught by a rude graffito scrawled with slate-pencil upon slate. It was of so concentrated, so stimulative, so penetrative a character — so thoroughly the voice of vice and passion in the proletariat — that it pierced the very marrow of my soul. "Prick to prick, so sweet"; with an emphatic diagram of phallic meeting, glued together, gushing. I must have seen a score such graffiti in my time. But they had not hitherto appealed to me. Now the wolf leapt out: my malaise of the moment was converted into a clairvoyant and tyrannical appetite for the thing which I had rejected five months earlier in the alley by the barracks. The vague and morbid craving of the previous years defined itself as a precise hunger after sensual pleasure, whereof I had not dreamed before save in repulsive visions of the night.

“. . . Inborn instincts, warped by my will and forced to take a bias contrary to my peculiar nature, reasserted themselves with violence. I did not recognise the phenomenon as a temptation. It appeared to me, just what it was, the resurrection of a chronic torment which had been some months in abeyance. Looking back upon the incident now, I know that obscene graffito was the sign and symbol of a paramount and permanent craving of my physical and psychical nature. It connected my childish reveries with the mixed passions and audacious comradeship of my maturity. Not only my flesh, but my heart also, was involved in the emotion which it stirred.”