A surprising and intense, I hesitate to call it a "symptom of grief," so maybe just "effect of my mom's death"? lately has been a visceral fear of death. How obvious could that be? But I didn't see it coming.

It's been said a few billion times, but the experience of watching someone die, of being in the presence of a person alive in her body, and then she's gone though her body remains, is deeply puzzling, disorienting, enough to turn one's thoughts to the spiritual. The mystery and sheer terror of the possibility of nothingness that that experience provokes might easily and neatly make a lifetime of confidence in the idea that consciousness is just a biological function sound, in one's head, like the contrariness of a third-grader. I mean, she was just gone. There. And then gone.

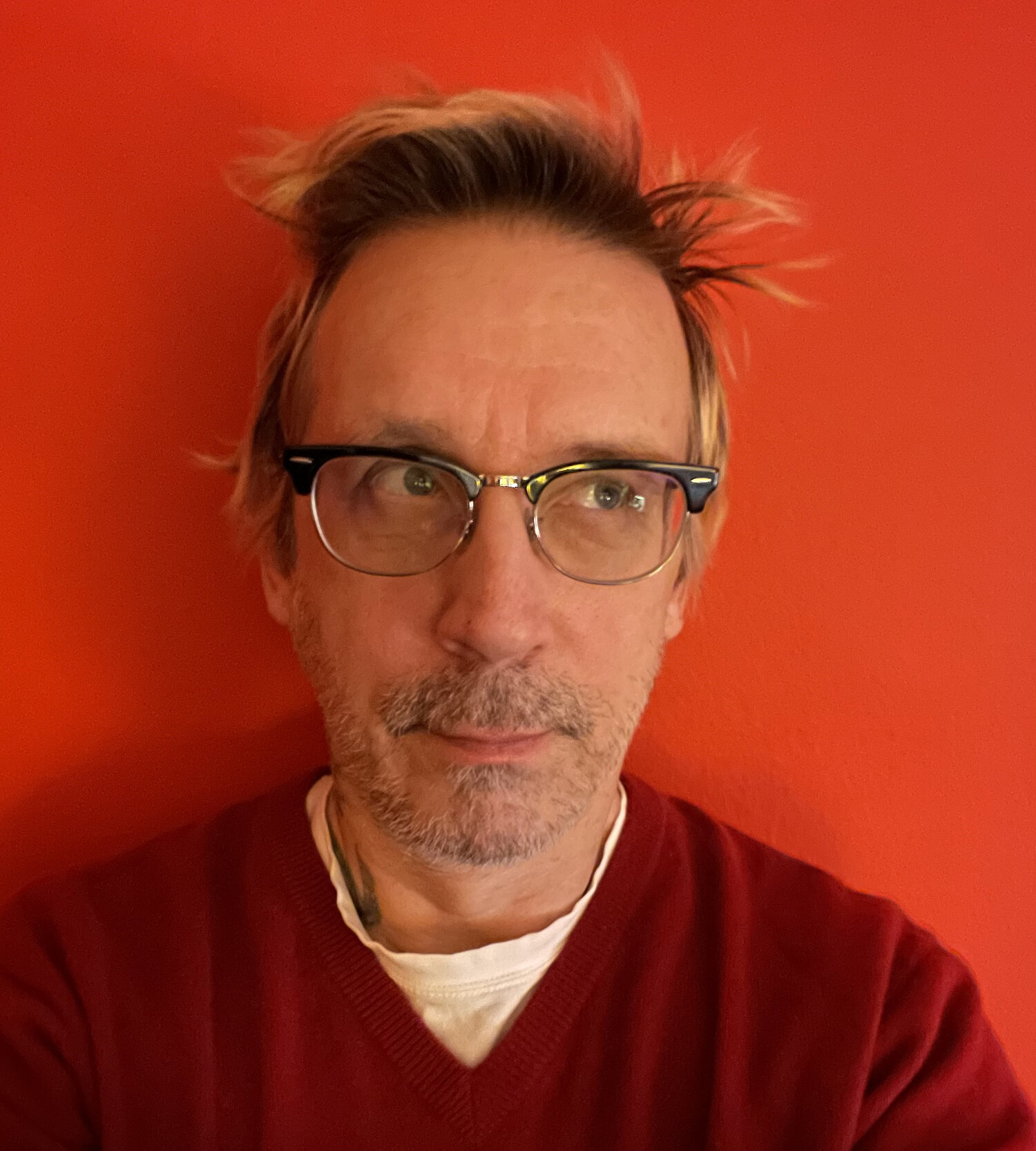

Mom was 75. I'm 54. That's not a lot of time. C gets mad at me when I say things like that, but he can't argue with the math.

Every night for years now I have, before I get under the covers, massaged my feet with lotion. I started doing it because I had dry cracked callouses, but it's grown into something else, a sort of meditation, a moment of gratitude for my feet, a little love for a body I'm not generally so charitable toward. In the period of time I've been performing this nightly ritual, the arthritis in my feet has gotten steadily worse. I spend the whole day beating my feet to shit, pushing the limits of the pain. At night they are swollen and sore and that massage before sleep some nights makes me feel like I could cry. I know it sounds weird but there's something moving about it.

Two weeks ago, I had surgery on one foot and next month I will have the same surgery on the other foot, to alleviate the effects of the arthritis. As my doctor puts it, "We go in, break the toe, put in a steel pin, scrape off all the extra stuff that's built up, and put it back together."

This is the first medical intervention into the aging of my body. And since aging is a linear process, it's the first of many. In other words -- though I consider myself lucky to have good health insurance, lucky to live in an age when many things that used to kill people dead are now small inconveniences, an outpatient surgery, an antibiotic -- it's all downhill from here. Knowing that 50 is the new 40 is not reassuring. Ten years go by quickly. I have a lot to do and not a lot of time to do it.

Speaking of aging, maybe it's just the particular alignment of my thoughts lately but I keep having encounters that make me feel dated, obsolete, like I live in a long-rejected paradigm, as if any contribution I may have made was a long time ago and now I'm just tolerated, allowed to linger, slightly embarrassingly, in a world I don't understand, let alone control, anymore.

I was in the elevator going up to the rehearsal studio last week, listening to a conversation between 2 young actors about what I don't remember except that it was littered with references to Starbucks, "when I was in line at Starbucks," "no, not that Starbucks, the one on 8th Avenue," "when she used to work at Starbucks," etc. The conversation was not about Starbucks, Starbucks was just a feature of the landscape of their lives. We -- I, others who've been here for a long time, people who remember -- rail against the incursion of chain stores in New York, but seriously, these kids don't care how I feel about Starbucks. Or Walmart, or 7-11. To them, complaining about Starbucks must make as much sense as complaining about sidewalks, or windows, or air. All our resistance to these things doesn't make them go away, will never change things back to how they were. And the people who arrived here to a New York with 3 banks and a Starbucks on every corner -- and fell in love with that New York -- would just be annoyed if it did change back.

Which leaves me feeling relief and despair in equal measure. There are 2 ways of looking at resistance. One is the Buddhist view that our resistance to, our clenching against, things we see as bad, rather than the thing itself, is what causes us pain. Or, along the same lines, the Quaker idea that "way will open," meaning that if we are on the right path, resistance will dissolve. But on the other hand, there's the more Judeo-Christian view that there are always evil forces opposing the good, the true, the right, and that we must remain strong, resolute, in our struggle to vanquish them. Which is it? Fuck if I know.

Another thing I've noticed the last few weeks is that everyone is talking about Blue Apron, which is this service where you pick out a recipe online and they deliver to you all the pre-measured ingredients to cook it at home. Finally, this thing -- cooking at home! -- that has been completely unmanageable for busy city dwellers, is within reach!

Nothing has made me feel more old-fashioned and less like everyone around me, recently. And not even in a stuck-in-the-80s way but more like a 50s Betty Crocker way, which is truly disturbing. Blue Apron's selling point is that it solves the problem people constantly cite about home cooking: too much waste. "I don't cook at home because you have to buy the whole head of celery when you only need 2 stalks, so I end up throwing the rest away." There's no waste if you, like, use the rest of the celery. I call bullshit. New Yorkers, who have to walk by steaming bags of foul, rotting restaurant garbage every morning on their way to the train can't tell me they're unaware of how much food restaurants throw away. It's not like I'm expecting people to buy a whole cow and feed themselves all winter, but is it really such an ordeal to keep a few pantry staples around and figure out how to get 3 meals out of a chicken?

(There's a great article in the Times today that touches on this subject. I don't know the writer, but the photos look like memories to me, and a few of the people in them were my friends back then. She captures something simple and vivid about what it felt like to come of age in New York, downtown, in the early 80s. I remember then having no doubt that New York was at the forefront of culture and that the East Village was at the very cutting edge of the forefront. That culturally there was no more advanced place anywhere in the world. And that was exactly the reason I wanted to be there and couldn't imagine being anywhere else. Arguably, it was true, but I think what I discovered by leaving the city for 12 years (1998-2010) is that it is true in a mostly superficial way. And it's left me with the infuriating and sort of useless feeling that no time and place will ever be as inspiring, as vivid, as eye-opening, as vital.)