One thing that’s not ideal about where I live is that the closest subway is a 15 minute walk. We’re right at the terminus of several bus lines, so sometimes we take the bus to the train, but, if the weather is friendly, I’ll walk. I’m a fast walker, New Yorkers are fast walkers, I don’t get much exercise otherwise, and I just kind of enjoy the quick stroll through my neighborhood.

A few weeks ago, I started to notice after a couple blocks a tight feeling in my chest, not exactly pain, but distinct pressure. Which was strange because, only a few days prior, Chan had complained of a similar feeling. I’d been very worried about him—chest pain is alarming—and I wondered if mine was some kind of sympathetic reaction. I didn’t say anything the first few times it happened; it felt ungenerous to steal his chest pain moment. At the very least, he was first in the queue.

But it seemed to get worse, and to happen sooner in the walk, bad enough that I’d have to slow way down for the last couple blocks, or stop altogether and rest.

Whatever was happening with Chan cleared up. His pain was triggered by deep breaths, and he figured it was probably a vestige of a bad chest cold he’d had recently. Mine got worse, so I made an appointment with my primary care nurse. My blood pressure was fine; it always has been. He did an EKG, which was normal. He referred me to a cardiologist, and I saw him on Monday of last week. The cardiologist scheduled me for two tests the following week (this past week), and he told me that if I had pain while I was resting, especially combined with numbness or pain in my left arm or jaw, light-headedness, etc. I should go to the emergency room.

On Thursday morning our housecleaner was here, and I walked to the neighborhood coffeeshop where I often work while she’s cleaning. It’s a 20-minute walk, but I took it very slowly. And then I walked home. I felt some pressure in my chest, but it subsided quickly once I stopped. That afternoon, I did some cooking, nothing crazy but I was on my feet for an hour or so, and the pain came back. I lay down on the couch, it didn’t go away, then my arm started to feel tingly, but both symptoms seemed mild, and I hemmed and hawed for a good half hour. I wasn’t in real pain and my pulse felt normal. But when I stood up, I felt faint, I got scared, and I decided I didn’t want to die of indecisiveness, so I called an Uber and went to the emergency room. Chest pain gets you past triage fast. Chan left work early and rushed over. They didn’t find anything wrong with me, and the pain was gone after a half hour or so. The doctor, nurses, a student doctor, lab technicians, everyone was lovely, kind, communicated clearly, but I was there for five hours, mostly sitting waiting for test results and discharge papers. I guess that’s just the nature of hospitals.

Back to the cardiologist on Monday. The first test was like a sonogram, or maybe it was a sonogram, with the wand and the jelly, but instead of a fetus it makes pictures of your heart. I asked the technician if she saw anything bad. She said, “The doctor will look at the images and discuss them with you,” which I’m sure is just the protocol, but I felt like there was something in her voice. Then, on Thursday, a “stress test,” which comprises a shorter version of the sonogram, then walking on a treadmill while you’re hooked up to the EKG electrodes so the doctor can monitor your heart activity while you’re walking, then another sonogram afterwards, to look at how your heart has reacted to exertion.

I was apprehensive about the treadmill. For a couple weeks, I’d been taking everything very slowly pretty much all the time because exertion triggers the pain. I’m not sure how long I was on the treadmill, it felt like only a couple minutes, when I had two jabs of sudden, intense pain in my chest and broke out in a cold sweat. The doctor pulled me off the treadmill and onto the examination table. I was terrified, he told me to take deep breaths, that I was okay, he was there monitoring everything, and he held my hand till the pain subsided.

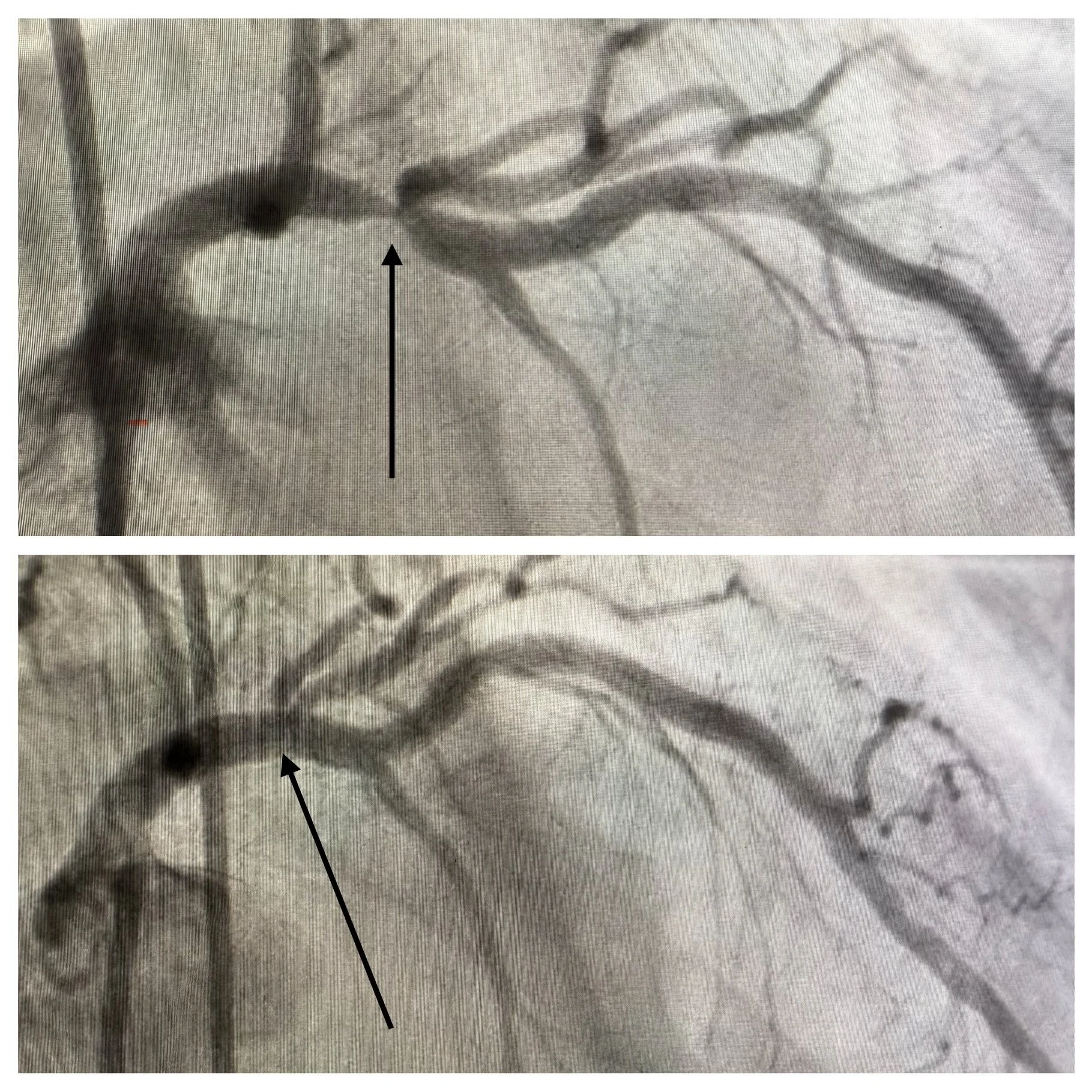

The cardiologist and the technician (maybe she was a physician’s assistant, I’m not sure) sat down in front of her computer monitor and looked at the blurry, grey moving images from the sonogram. Two of the images in particular they watched several times over, and I swear I saw their faces darken. They looked at each other, concerned. The doctor came over and stood facing me and said, “Based on your symptoms, the changes in your heart activity concurrent with the pain, and the sonogram images, I believe you have “significant coronary disease.” I have “blockages” in my coronary arteries.

High cholesterol runs in my family. We all have it, my siblings, my mother. I’ve battled it all my life—that’s not true, I should say I’ve battled it during the intermittent periods of my life when I’ve had health insurance. I take a statin drug for it now, a high dose, and the number is still higher than it should be. But I’m the first that I know of to have heart disease. Somebody has to be first.

Monday morning at 6:30, I will have a procedure called a “heart catheterization” at Mt. Sinai Hospital on the Upper West Side. It’s another diagnostic test. They’ll insert a tube into a vein in my wrist and feed it up into my heart to deliver a contrast dye, and then they’ll take x-rays. It’s to locate and assess the extent of the blockages. Depending on what they find, I’ll have one of four possible courses of treatment: One, they find no blockage (extremely unlikely based on the previous tests and my symptoms); two, the blockage is minor enough to be treated with drugs (the cardiologist says this is also very unlikely, based on the above); three, they find blockages in one, or two, arteries (in this case, they’ll place a stent or stents to open up the artery, as part of the procedure, since they’ve got the tube up in there already); and four, they find extensive blockages and/or blockages in the main coronary artery (the treatment in this case is bypass surgery—they’ll wait till I’m awake from the anesthesia to discuss this with me). I think with the stent I would go home that day. With the open heart surgery, I would be in the hospital for a week.

This is all moving kind of fast, and I wanted to get all the details down before I start to forget or make things up. I’m used to telling everybody everything, but for weeks all I had was chest pain and uncertainty to share. I waited even to tell my friends and family until there was something concrete to say. And then suddenly I had bad news, or at least dire news. I’m looking forward to Monday and getting on with it. I won’t say I’m not very frightened (and these few days of waiting are excruciating).